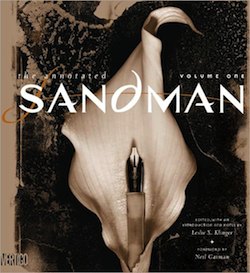

There have been several iterations of Neil Gaiman’s iconic graphic novel series, The Sandman, from the original single issue run to the collected trades to the luxurious Absolute editions—and now, though Gaiman had initially intimated that he would prefer it not to happen while he was still around, there will be a truly delightful, extensive, intimate set of annotated editions, if the first volume is any indication. The annotations are handled by Leslie S. Klinger of The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes and The New Annotated Dracula renown; Klinger is also a friend of Gaiman’s and a fellow associate in the Baker Street Irregulars.

The first hardcover volume contains issues #1-20, reproduced in black and white, with extensive annotations on a page-by-page, panel-by-panel basis, including quoted sections from Gaiman’s scripts, historical references, DC Universe references, and linguistic notes, among other things. The introductions, by both Gaiman and Klinger, are revelatory of the intent and emotion behind the project, each explaining why it’s happening now, and what went into getting it done. It’s a handsome, big book—a bit difficult to curl up with, but beautiful.

Gaiman’s introduction deals with the impetus behind the project and with the occasionally uncomfortable intimacy of having the annotations done—”I gave Les the scripts to Sandman. This felt a strange thing to do—they were very personal documents, each one a letter to the artist who would be drawing it, each more personal than I was comfortable with.” It also deals with his personal relationship to Klinger and the history of other, unofficial Sandman annotations. The reason this book came into being now, as opposed to in a distant future, is that Gaiman forgot a reference when asked about it by a reader, and decided that it was time to get to work on the annotated editions. He says he called up Klinger to tell him:

“‘You know I said you should wait until I’m dead to annotate Sandman,’ I said. ‘I’ve changed my mind. You should do it while I can still remember things.'”

Klinger’s introduction tells the same story from a different angle, but also introduces his methodology in creating the first true annotated graphic novel, with “detailed notes that would be reproduced on the page next to the panel.” It’s quite the project—in some ways like any other literary annotation, and in some ways all together different, as necessitated by the cooperative medium of comics (and, also, working with an author who is still alive to make corrections and offer explanations).

I discuss these introductions because they provide the framework for what follows, and shaped my reading of the project—as cooperative, intimate, and immense in its referential scope. The comic itself has been critiqued and reviewed a thousand times, so here I’d like to focus on what makes these volumes unique: Klinger’s annotations. First comes his essay “The Context of The Sandman,” which briefly examines the origin (as transcribed by Gaiman in a column) and cultural context of the Sandman graphic novels, and then the issues themselves.

I’ve read Sandman multiple times; I own the Absolutes and the trades. I couldn’t resist the opportunity to lay hands on The Annotated Sandman: Volume 1 when given the chance, though—I have a weakness for annotations and facts that I suspect many a book-nerd shares with me. For those readers, this book is a festival of treats, a total delight; Klinger’s work is precise and wide-ranging, bringing to life aspects and levels of the scripts that were previously hidden in shadowy allusions or minuscule visual cues. I’m not certain it would have the same effect on a first-time reader of the series, but once they’ve had a chance to read the comic through and come back around to the annotations, the experience should be the same. (An aside: I would recommend a first-time reader peruse the new trades or the Absolute editions initially; while the black and white printing is stark and fascinating for a re-read and lowers the printing cost of this book considerably, the colors are a sight to behold, and shouldn’t be missed.)

Some issues have more annotation than others—the most complex was “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” (#19), which had so many notes regarding historical personages and locations that they frequently ran onto the following page, and the least was probably “A Dream of a Thousand Cats” (#18). There are occasional photographs included where appropriate (in black and white, as is the rest), like the covers for the “The House of Secrets” and “The House of Mystery” comics, Auguste Rodin’s unfinished sculpture The Gates of Hell, and Elsa Lanchester in The Bride of Frankenstein. There are also a huge amount of allusions to DC continuity, far and above those I caught in my previous readings, that Klinger not only notes but provides context for—publication dates for the comics the references originate in, character names, backstories and connections, et cetera—but also how they tie into the world of The Sandman. The DC references slowly filter out as the series continues and becomes more divorced from the universe, but in this first volume, there are quite a lot.

For example: 14.3.1, the annotation on the missing serial killer who goes by “The Family Man,” explains that he was a “notorious British serial killer [ ] dispatched by John Constantine in Hellblazer, issues 23-24, 28-33,” and that that’s why he’s missing and the Corinthian can take his guest of honor spot. It’s a brief reference in the comic, and it’s not necessary to know that “The Family Man” was from another comic, was killed, and that’s why he’s absent—the plot works regardless of that knowledge—but it adds a level of richness that Gaiman was making so many intertextual references, not just the obvious tie-ins.

My favorite bits of the annotations, however, are the quotes from Gaiman’s notes and scripts. They’re a startlingly personal portrait of his internal landscape as he was writing these issues, a view into the creative mind of a younger man, a much younger writer, who was not entirely confident in his capabilities. In particular, the notes on “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”—the only comic to ever win a World Fantasy Award; one of the most well-known issues of The Sandman—were revelatory. About the way the comic will play out, he says: “I think it’ll work, but then, on a bad day I think Sherlock Holmes really existed and that peanut butter sandwiches are trying to tell us something, so what do I know?” (19.7.7). But, better yet, on 19.12.1:

“NG comments in the script: ‘This is a fascinating comic to write. I mean, either it’ll work really well, or it’ll be a major disaster. Not just a disaster. I mean people will talk about this in the list of great interesting failures forever. They’ll say things like ‘Cor! You call the Hulk versus the Thing in three-dee pop-up graphic novel with free song-book an interesting failure? You shoulda been there when Gaiman and [artist Charles] Vess made idiots of themselves on Sandman!’ or, like I say, it may work. (It’s a million-to-one shot but it might just work )”

I had to pause for a bit after reading that and smile. How personal, the uncertainty of how well this brilliant story was going to work—seeing it from the inside, from Gaiman’s eye, is so very different than seeing it as a finished product. Other script quotes are simply amusing, such as his awkward story about the S&M club that inspired the nightclub in Hell. All of them are immediate and intimate, as if Gaiman is speaking directly to you (and, as they were written directly to the artists, that makes a lot of sense), adding a depth of feeling to the comic that already has such an immense weight of culture and acclaim behind it. The real value of Klinger’s choices for what to show us as reader and what not to of Gaiman’s notes is that he chooses delicately, selectively, to construct an alternate way of reading the stories: not just as we have known them, but as only Gaiman knew them.

The other sets of references that I found intriguing were the mythological and cultural notes, annotations that deal with the huge amount of myths and legends that Gaiman employs, adapts, and subverts. Especially interesting was that in the African myth issue (#9), Gaiman makes up a name for a trickster god—whereas there are certainly real ones that he could have used instead, including Anansi, whom appears in Gaiman’s later novels, American Gods and Anansi Boys. Klinger lists other trickster gods and their origins in addition to exploring the linguistic breakdown of the name Gaiman invented. That sort of thing is just thrilling for me; I love the linguistic annotations, too. Great stuff that adds so much to my reading of the comic, all of it.

There are also the few notes on errors or inconstancies that crop up, where Gaiman’s dates don’t match historical dates, mostly—things that I would have never noticed, but are interesting to see. Also, titles that don’t match between the “next week” at the end of one issue and the next issue itself, of which there are a few. The bibliography is detailed as well, ranging from Shakespeare’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” to interviews with Gaiman to books on mythology.

I will note that there are a couple of points at which the formatting for the annotations is slightly skewed—for example, in 6.12.7’s annotation, a line is included that actually refers to 6.14.7, the next left-facing page. It seems to have been a publisher formatting error, as the annotation is correct, it’s just placed in the wrong column. Other than that error and one more like it, The Annotated Sandman: Volume 1 is remarkably clean copy, concise as possible while still encompassing all of the information that Klinger needed to convey about the issues, their art, the panel arrangement, the background, and so on.

As a whole, I am impressed and satisfied by Leslie Klinger’s fabulous work on these annotations, covering as they do so much information, and information of such wildly different varieties. The end result is a reading experience unlike any other I’ve had with The Sandman—the lens Klinger has given me to read through is multifarious, multifaceted, and deep. It is at once stunning—Gaiman’s research went further and wider than I had ever imagined or been able to grasp—and intellectually satiating, creating a rich reading experience that is well worth every penny of the cover price for the volume, whether or not you may already own (as I do) this comic in other formats. I fully intend to pick up the next three volumes and continue the journey of re-reading this comic in a new, complete, curiosity-satisfying way.

Frankly, I’m thrilled that Gaiman decided it was time for this project to happen and that Klinger was ready and willing to apply his research skills to it. The Sandman is one of my favorite comics, and The Annotated Sandman is only an improvement on my initial pleasure in the work. I recommend it, highly.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic and occasional editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. Also, comics. She can be found on Twitter or her website.